Do banks have a responsibility for levy contributions? A South African perspective

In the state of New South Wales (NSW), Australia, legislation imposes specific responsibilities on banks and other financial institutions, when they take possession of sectional title units (referred to as ‘strata lots’) after foreclosure.[1] These financial institutions share liability with the owner for unpaid levy contributions, including regular and special levies, as well as interest on arrears and associated debt enforcement costs incurred by the body corporate (referred to as the ‘owners corporation’ in NSW). This provision ensures the financial health of strata schemes. By mandating such responsibilities, the SSMA creates a safety net that protects communal resources, protects property values, and ensures that community schemes can sustain themselves financially until a paying unit owner takes ownership.

In contrast (and potentially, regrettably) in South Africa, no equivalent provision exists in its sectional title laws,[2] not even for banks ‘in possession’ of sectional title units. This gap leaves sectional title schemes, paying unit owners, and other stakeholders vulnerable, perpetuating a cycle of financial instability, which often leads to property / urban decay and the erosion of value. This gap is particularly concerning in light of the increasing urban decay afflicting many cities and towns across South Africa. As we all know so well by now, the non-payment of levies undermines the financial viability of bodies corporate, leading to deferred or no maintenance, reduced service quality or no services at all, and deteriorating communal property. These outcomes drive down property values and create a domino effect that further destabilises the urban landscape. Municipalities then suffer rates revenue losses, and the city deteriorates further. Over time, these challenges can erode not only the sectional title scheme itself but also the surrounding neighbourhoods, compounding the social and economic toll.

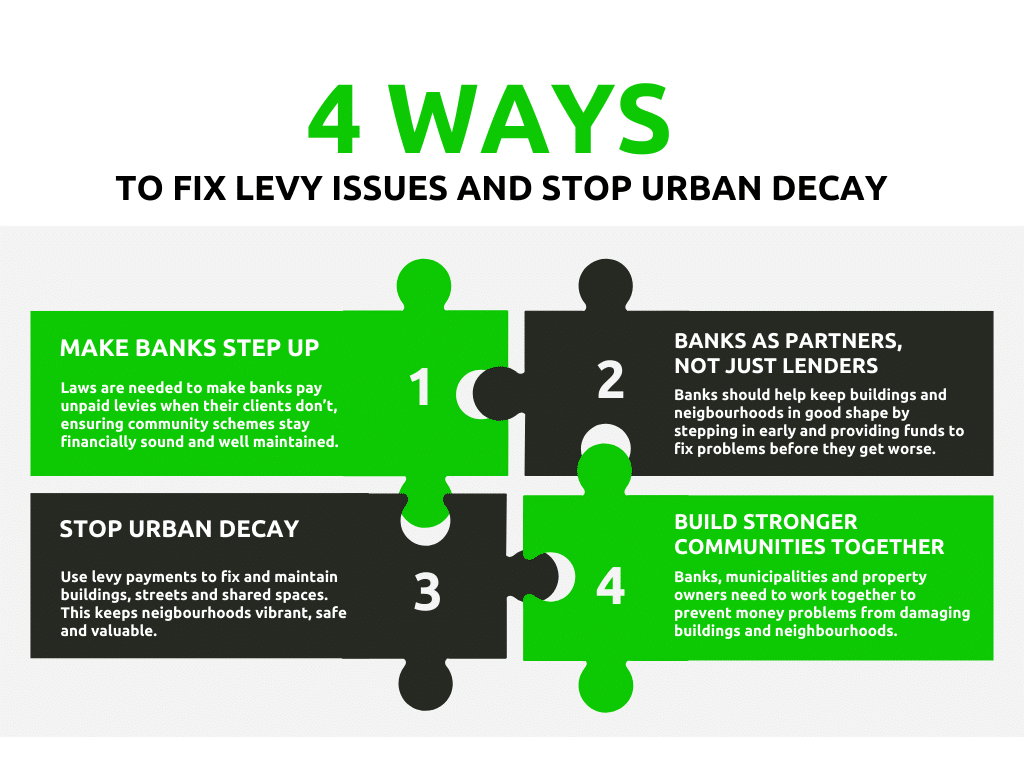

However, this challenge also presents an opportunity: to lobby for the introduction of a necessary and timely concept – requiring banks in South Africa to cover levy contributions when their clients default, and not only when the bank is in possession of the property, such as in foreclosures. While retrospective application to arrear levies might be legally unfeasible, implementing such a provision going forward could significantly stabilise bodies corporate and prevent further property degradation. It also makes sense for other reasons as we will elaborate on below.

Given these realities, would implementing some statutory reform that holds banks jointly responsible play a pivotal role in stabilising sectional title schemes and mitigating urban decline?

Addressing potential bank concerns

The immediate reaction from financial institutions might be that such a measure could lead to an increase in defaults, forcing banks to act more quickly, potentially selling or acquiring properties in possession. This concern can be mitigated by leveraging existing legal frameworks, such as the embargo provision,[3] which requires sellers and purchasers to clear arrears for levy clearance certificates to effect transfers at the deeds office (whether the sale occurs at a public auction by the sheriff, or otherwise).

Banks often end up indirectly exposed to end costs in possession cases, whether through increased bond amounts taken out by purchasers to cover the seller’s arrear levies or through the financial strain placed on bodies corporate. In some instances, bodies corporate may resort to compromises that distribute the financial burden of unpaid levies across paying unit owners, potentially forcing an unlawful loss situation. A proactive adjustment to include levy obligations alongside monthly bond payments could help mitigate these risks, ensuring a more equitable distribution of financial responsibility. This approach would also safeguard the financial integrity of sectional title schemes and reduce the ripple effects of default on paying owners and broader community dynamics.

By understanding this financial obligation upfront, banks can incorporate levies into affordability assessments under the National Credit Act[4] (‘the NCA’) before approving a bond. This approach aligns with their responsibility to assess borrowers’ repayment capacity, anyway, and helps protect both their interests and those of sectional title schemes and the broader public. Adjustments such as lowering the loan-to-value ratio could further reduce the risk of defaults and / or provide an excess buffer when a unit does in fact fall into arrears, safeguarding paying unit owners and preventing dilapidation of communal property.

What are the benefits of such a Statutory Amendment?

- Stabilised financial health of sectional title schemes

Holding banks accountable for unpaid levies of a sectional title unit owner would ensure a steady inflow of funds to the body corporate. This provision would strengthen the ability of schemes to maintain and improve the common property.

- Improved risk management for banks

Sectional title schemes enjoy a statutory preference over mortgage bonds during liquidation or sequestration (‘the embargo provision’). Ensuring sectional title levies are paid minimises outstanding liabilities ahead of realisation of the asset by the bank, or other creditor, thereby reducing potential credit losses for banks. They could, of course, still lose. But at least they could take earlier action if they were notified that their client, the unit owner, is failing to pay levies and putting the bank at financial risk.

By incorporating levies into monthly obligations, banks gain early warning signals of financial distress. This proactive approach could lead to faster foreclosure actions or support mechanisms, ultimately reducing credit losses.

- Enhanced buyer and owner education

Banks, incentivised by this potential liability, would likely take greater responsibility for educating borrowers on the importance of timely levy payments to their bodies corporate (maybe even credit risk insurance could step-in), at the time of bond origination. This could lead to a cultural shift, fostering financial discipline among sectional title owners, who become financially savvy as a result. As highlighted by a recent article written for the Mail & Guardian by Tia-schae Ramparsad (‘Ramparsad’), banks currently focus on a buyer’s ability to repay a home loan, often overlooking levies as a critical financial commitment.[5] Ramparsad makes the following additional points, among others:

- To provide buyers with a more realistic view of their long-term financial commitments, banks should collaborate with bodies corporate to project levy increases over a 10- to 20-year period.

- New homeowners require greater transparency and education about these costs, as many are unaware of the potential for substantial levy increases.

- Prospective buyers should be encouraged to assess the financial health of an estate by reviewing levy statements, budgets, and meeting minutes, rather than being solely influenced by glossy marketing materials.

- By promoting transparency and fostering informed decision-making, banks and bodies corporate can contribute to the creation of fair and compassionate policies that balance the needs of communities with the financial realities of individual owners, ensuring that gated communities remain accessible and sustainable.

- Reduced dilapidation and urban decay

A well-maintained scheme is more likely to retain its market value, making it easier for owners (and banks, bodies corporate and other creditors) to sell units in financial distress, which ultimately suits the banks, thereby potentially avoiding sequestration or liquidation.

Recommendations

To address these challenges and opportunities, South Africa, in conjunction with mortgage lenders, should consider introducing similar safeguards and liability to what is available in NSW.

Mortgage bondholders should share liability for:

- Outstanding levies (regular and special contributions);

- Arrear interest on outstanding levies; and

- The reasonable costs of recovering unpaid contributions.

Moreover, the enforcement mechanism should include:

- Mandatory written notifications to banks once a levy falls into arrears (i.e., it is vital that the respective bank is advised immediately following a default of a levy by a unit owner, to ensure that they can act decisively);

- Automatic assumption of liability by the bank after a set notice period, or after judgment or adjudication against the unit owner.

Should banks be liable for historical arrears?

A provocative question arises: Should banks be liable for historical arrears where the bond is being serviced by the unit owner, but levies are not? This happens often as unit owners prioritise the big banks over the small body corporate. This concept introduces an intriguing dynamic, as the bank ultimately stands to lose if arrears undermine the saleability or value of the sectional title unit. Why not require banks to settle the full extent of levy arrears, thereby allowing the sale to proceed, satisfying levy clearance requirements, and transferring the net liability to the bank?

This approach could be the sting in the tail needed to hold banks accountable when they fail to monitor or address cases where a unit owner prioritises bond payments over levy obligations. Such oversight undermines the principles of community living and shared responsibility. The bank, as an interested and invested party, should rank second in payment priority after the community scheme’s levies and not just when the community scheme finally enforces the debt through the arduous debt enforcement processes available to it.

Should the cost of sectional title ownership fall primarily on the community scheme, or should banks share this responsibility? It is worth exploring mechanisms allowing schemes to claim against the bond for unpaid levies, either when the bond is being serviced or when neither the bond nor levies are paid. This could function as an “access facility” for levies owed by the unit owner, providing immediate financial relief to struggling bodies corporate while protecting the community from the cascading effects of arrears.

However, such a proposal opens Pandora’s box. It challenges entrenched priorities and raises complex questions about the balance of liability and responsibility. How far down the rabbit hole can we go, and where do we draw the line? What most will agree on, is that the line must move.

Call to Action

The financial responsibility of banks in South Africa’s sectional title schemes should not remain a missed opportunity. Introducing shared accountability between banks and their clients could revolutionise the management of sectional title schemes in South Africa and improve the property sector. Lobbying efforts should focus on amending the sectional title laws to incorporate provisions that safeguard the financial and structural integrity of sectional title developments. While banks might initially resist such reforms, the long-term benefits – reduced defaults, stronger collateral, and improved urban conditions – are undeniable. By taking proactive steps to support sectional title schemes, banks not only protect their investments and lending, but also contribute to the sustainability of communities across the country.

The urban decay in the cities may improve over time and probably won’t get worse if banks had to step in and share liability with their clients. Other ways could be that the bank can take earlier foreclosure decisions, stemming the bleed and rot that has been exacerbated over time by under-resourced sectional title schemes and courts / CSOS for the required debt enforcement procedures.

Let this serve as a call to action: it is time for stakeholders to advocate for a fairer and more robust framework that places shared accountability at the heart of sectional title management and to champion legislative changes that ensure the resilience and growth of South Africa’s property sector.

Are you in need of expert legal advice? Our specialist legal team is standing by to support and guide you with all your “complex” issues. Reach out to us!

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Section 84(2) of the Strata Schemes Management Act 50 of 2015 (NSW).

[2] Sectional Titles Schemes Management Act 8 of 2011 and the Sectional Titles Schemes Management Regulations, 2016.

[3] Section 15B(3)(a)(i)(aa) of the Sectional Titles Act 95 of 1986.

[4] Act 34 of 2005.

[5] Tia-Schae Ramparsad, Mail & Guardian ‘Levies are the pitfall of living behind gated walls’, 5 November 2024. Accessible at https://mg.co.za/thought-leader/opinion/2024-11-05-levies-the-pitfall-of-living-behind-gated-walls/.